After decades of stories in Southern California claiming chemical companies had regularly dumped toxic waste into the waters of the Pacific, a group of marine researchers deployed maritime drones to look for signs of substantiating evidence. They found more than they bargained for: over 27,000 metal barrels on the ocean floor, many if not all of which were originally filled with DDT and other poisonous matter.

Autonomous drones map gigantic ocean toxic dump

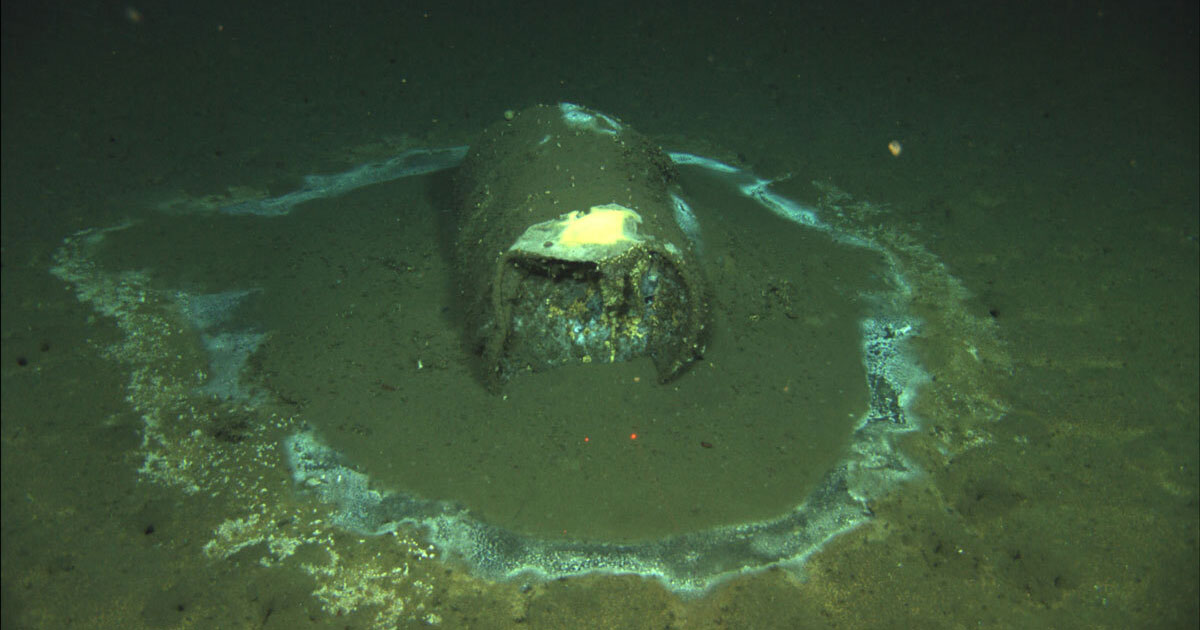

The discovery was the work of UC San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography, which dispatched two underwater drones to map 46-square miles of seafloor between the Santa Catalina Islands and Los Angeles coast. During that operation last March, autonomous underwater vehicles (AUV) used high-frequency side-scan sonar at depths of 3,000 feet to uncover the enormity of the toxic threat researchers had wanted a peek of. What they revealed were more than 27,000 metal barrels – just a portion of the over 100,000 objects identified as debris without being similarly confirmed as waste receptacles. During at least one targeted AUV dive, cameras captured fluorescent materials leaking from the decaying containers.

Reports of dumping had not only been true, researchers realized, but had enormously underestimated the scale of the disastrous practice.

“Unfortunately, the basin offshore Los Angeles had been a dumping ground for industrial waste for several decades, beginning in the 1930s.” Eric Terrill, chief scientist of the expedition, said in a University of San Diego report on the expedition. “Now that we’ve mapped this area at very high resolution, we are hopeful the data will inform the development of strategies to address potential impacts from the dumping.”

It had long been conventional knowledge around Southern California that local chemical companies had started dumping surplus or toxic waste – notably DDT and PCBs – into the Pacific even before World War II. Review of company shipping logs over the years in some cases substantiated allegations of the practice, which continued until the 1972 passage of the so-called Ocean Dumping Act banning it. It took far longer to quantify that assault on the environment.

Cutting-edge drone tech reveals enormity of toxic threat

In 2011 and 2013, UC Santa Barbara professor David Valentine documented concentrated levels of DDT in sediment in the same area the Scripps expedition has now mapped. His findings coincided with rising levels of toxins in local sea mammals. Valentine’s work identified 60 chemical containers. In 2020, the Los Angeles Times published a blockbuster report on the regular ditching of unwanted poison into the ocean, yet even then few imagined how huge the dumping had been.

“In hindsight, we shouldn’t have been surprised,” said Terrill. “But it’s one thing to read historical reports that there may be tens if not hundreds of thousands of barrels on the seabed. It’s another one to start counting those in acoustic side-scan data.”

The capacities of the AUV, and powerful tech aboard, made detection and precision mapping of the polluted seafloor possible in ways that hadn’t existed before. The drones automatically adjusted to seafloor topography, navigating at a constant 20 meters above the bottom. Their side-scan sonar sent signals 150 meters to each side, and were calibrated to detect objects as small as a coffee cup.

The result was 100 gigabytes of data generating an accurate map of the floor, the size and shape of debris dumped onto it, and some indication of how much individual DTT-filled barrels have decayed. With that accurate information revealing just how vast and enduring the human recklessness was, Scripps will now study whether the toxic matter can be exhumed from the seafloor, and how poison that has leaked out is being processed by the ocean and its food chain.

FTC: We use income earning auto affiliate links. More.

Comments