Despite surging tech advances that allow drone makers to both reduce craft size and increase their onboard capacities, one vexing problem remains: The more apped-up uncrewed aerial vehicles (UAV) are shrunk down, the less able they are to withstand adverse events like wind gusts and collision. That may soon change.

Insect-sized drones resist turbulence, collisions

Researchers have developed drones so small they could feasibly pollinate crops or dodge in and out of slim openings to inspect complex infrastructure – even in windy situations. In that way, they promise to combine the utility and mission effectiveness of larger drones with the agility and resiliency of mosquitos (without the annoying bites and potential diseases). And because their tiny wings flap at rates of nearly 500 beats per second to keep the six decigram craft aloft, the nano-UAV can respond to and recover from sudden gusts – or worse – in ways larger, rotor-lifted vehicles can’t.

“You can hit it when it’s flying, and it can recover,” says Kevin Yufeng Chen, an assistant professor at the Massachusetts’s Institute of Technology’s (MIT) Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science and the Research Laboratory of Electronics. “It can also do aggressive maneuvers like somersaults in the air… If we look at most drones today, they’re usually quite big. Most of their applications involve flying outdoors. The question is: Can you create insect-scale robots that can move around in very complex, cluttered spaces?”

The work by Chen and his co-researchers at Harvard and City University of Hong Kong suggest they can – or will before too very long.

Aiming for outdoor agri, and confined space industrial use

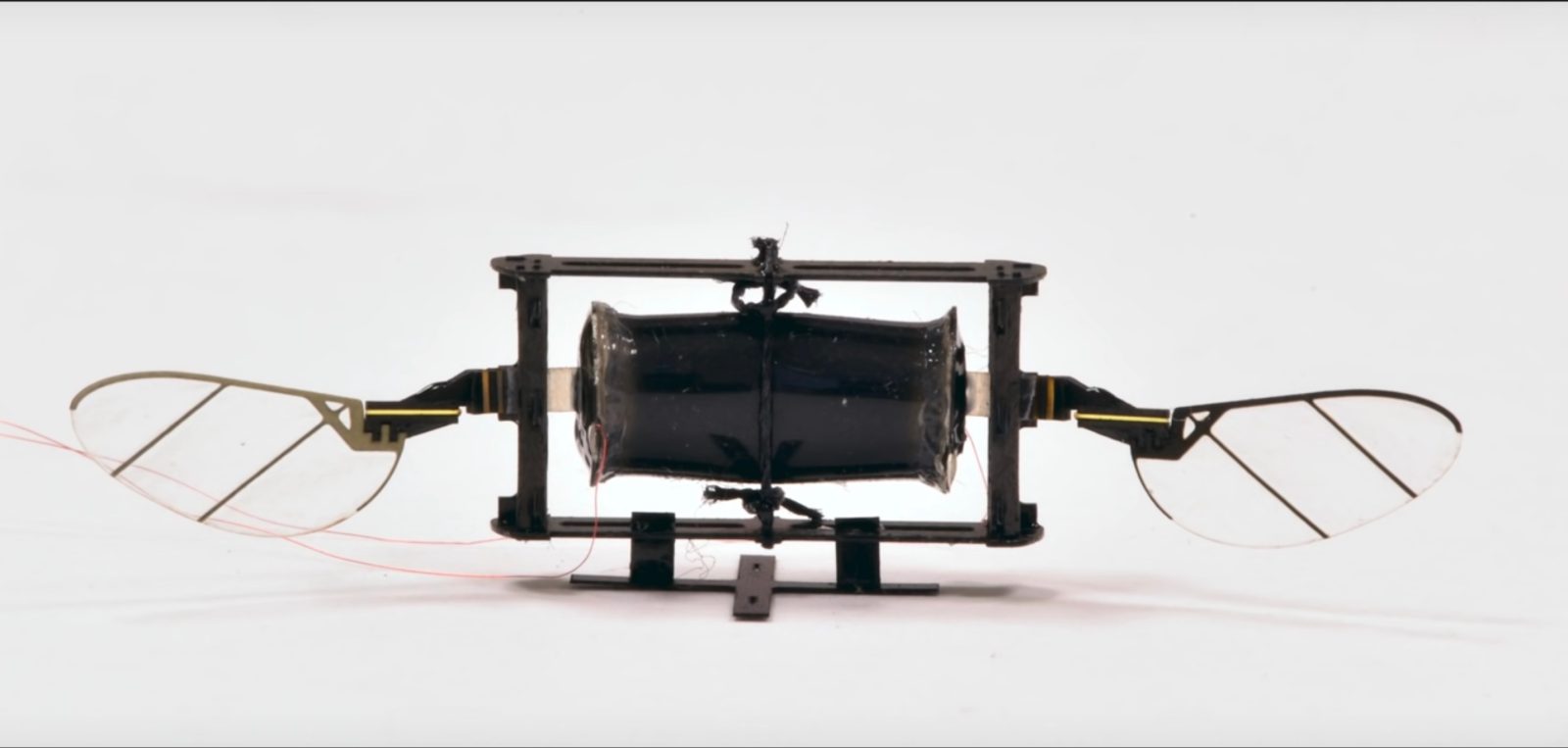

The central element to their gnat-drone prototypes are small rubber cylinders covered in carbon nano-tubes. Electrical charges to the surface cause the rubber to expand and contract, supplying the rapid movement that beats the craft’s wings. Though the US Air Force recently announced a project to develop wing-flapping insect-sized drones for surveillance purposes, those craft apparently won’t be designed to operate in confined spaces.

Chen considers attaining that enclosed operational objective vital in order to create tiny drones capable of offering a wider range of enterprise solutions.

“Think about the inspection of a turbine engine. You’d want a drone to move around (inside) with a small camera to check for cracks on the turbine plates,” Chen told MIT News, adding the bumblebee-sized craft will also be developed for agricultural work like plant pollination, and search and rescue missions. “All those things can be very challenging for existing large-scale robots… The challenge of building small aerial robots is immense (so) you need to look for alternatives.”

FTC: We use income earning auto affiliate links. More.

Comments