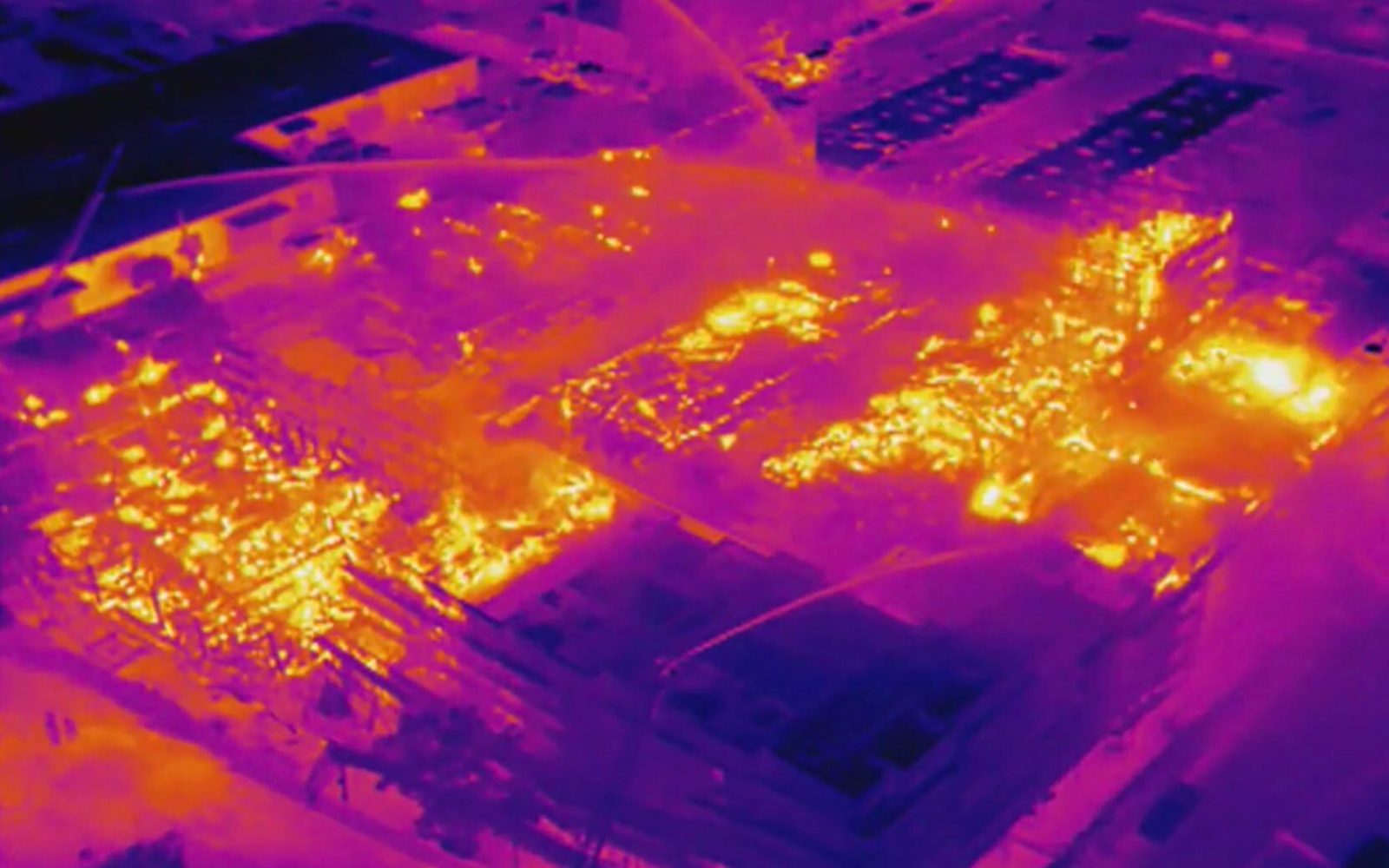

Enterprising officials from the Minnesota town of Warren are using drones equipped with thermal sensors to gauge heat seepage from local buildings and houses as part of a public service to help homeowners cut spending on energy.

The scheme was described by Warren City administrator Shannon Mortenson on the Institute for Local Self-Reliance’s energy affairs podcast. The town is a member of the Climate Smart Municipalities Partnership, in which cities in Minnesota and Germany link up in sustainability and climate initiatives. Warren and its German oppo, Arnsberg, decided to map out their respective cities to create an accurate profile of structural insulating inefficiencies and varying losses of heat. To do that, Warren decided to fly drones equipped with thermal sensors, then combine the different photos together until they had a full municipal map.

Since costs – or more accurately, avoiding as many of those as a medium-sized Midwestern town can take on – were a concern, officials recruited pilots from Northland Community College in the neighboring town of Thief River Falls. The school had founded a drone program as part of its educational offer, and students in it began flying thermal-reading drone missions in 2017. It took a lot of time, and trial by error, to put the resource together.

The drones are flown at altitudes of 200 feet, but for the thermal sensors to get accurate readings, missions must take place when it’s cold enough for furnaces to be operating – but not below the 32 degree threshold where UAV operation and battery life begin to suffer. Outings must also avoid significant winds, which in Minnesota meant limiting mapping season to a few weeks each year in late autumn.

Over time, the pilots fine-tuned timing of flights even more. When drones’ thermal sensors scanned houses towards the end of the day, heat soaked up by rooftops from the sun looked identical to energy leaking. It was therefore decided to fly missions late at night for clear readings during periods when seepage tends to be greatest.

Once a sufficiently complete map was available to provide an accurate picture of the town’s heat-leaking structures, owners of homes and office buildings were invited to learn about their levels of energy loss. Those who request that information then learn of the various solutions available to cut down on that waste, and are offered several municipal-backed financing schemes to make those improvements possible. One of those grants work loans to applicants, who then reimburse money each month using the savings they realize on each month’s energy bill.

That collective effort to decrease energy waste came naturally to Warren. The town owns its non-profit utilities, including electric and gas. That setup makes city administrator Mortenson responsible for oversight of the city’s energy reserves – and a logical person to head the town’s energy-loss mapping mission.

“I think it’s just good to have a handle on where’s your energy loss in the community, and how can we be more efficient,” Mortenson explains. “How can we be good stewards and try to mitigate climate change and increase sustainability in our community? Our plan is to take that data and allow residents to come in, sit down with staff and see where their greatest energy loss is in their homes… That way they can make a decision that would give them the greatest energy savings and cost savings.”

With word of the program spreading, municipalities in Texas, Illinois, and Iowa questioned Warren about the replicating the project – even those without local community colleges with ready-to-loan thermal sensor-packing drone fleets, or the keys to their own utility companies. Score it as yet another example of both drones, and elected officials for good.

FTC: We use income earning auto affiliate links. More.

Comments