Will the portion of the National Defense Authorization Act containing a ban on drones made by China-based companies like DJI be the boon for US makers the law’s political backers claim? “A definite maybe” is what a reading of a new document detailing the measure published by longtime UAV expert and innovator Mark Bathrick offers readers.

As DroneDJ reported after its legislative approval in December, the $886.3 billion National Defense Authorization Act for fiscal year 2024 was fitted with the previously independent American Security Drone Act of 2023. Within that latter element is the de facto blacklisting of UAVs on US entities lists, thus prohibiting their procurement and official use by government agencies or employees. Supporters alternatively cited – without providing any accompanying evidence – data leaking to, complicity in human rights abuses with, and partial ownership by China’s government as justification for targeting DJI, Autel, and other companies.

Both firms have rejected such allegations as entirely unfounded.

President Joe Biden’s signing of that bill into law December 22 represented a victory for the measure’s large (and decidedly opportunistic) group of backers in Congress, a body ever eager to burnish its otherwise shocking unproductivity in ushering legislation to completion – nominally its main activity in office It also allowed them to score points with voters aware of the acidic diplomatic relationships with Beijing by offering protectionist succor to US companies habitually left in the dust by China-based drone maker DJI.

Better still for the Team USA aerial pep group, the new prohibitions on federal use of the most popular and technologically effective drones come just as the Department of Defense is moving forward with its Replicator program. That plan to swamp enormous arms platforms of foes like Russia and (wait for it) China with dense UAV swarms is expected to dramatically increase the orders and output of domestic defense and security small UAV manufacturers.

All is therefore just grand for US drone companies and really stinks for DJI and Autel – especially awaiting yet another pending bill that could effectively ban even owners of consumer UAVs from China from operating in US skies.

Absolutely, albeit maybe not really, suggests a reading of a tutorial on the law by Bathrick Aviation Consulting.

Run by former Navy fighter pilot and “Drone Meister” of US government aerial operations, Mark Bathrick, the consultancy’s “What Does the American Security Drone Act Mean for You?” guide offers an objective, matter-of-fact examination of the law: its prohibitions, and – significantly – its exceptions. As such, it cuts through the inaccessible legalese politicians rely on to produce legislative sophistry designed to perplex people faster than Finnegan’s Wake, and catalogue what the legal restrictions and loopholes are.

Bathrick’s listing of those elements includes – among other things – exceptions that otherwise chest-thumping pols have created to permit federal UAV users to shrug off the blacklisting of DJI and Autel craft. Of course, final proof of the new legal pudding will only become clear as it’s served up over time, but the guide suggests the law won’t be the lights-out blow its cheerleaders suggest.

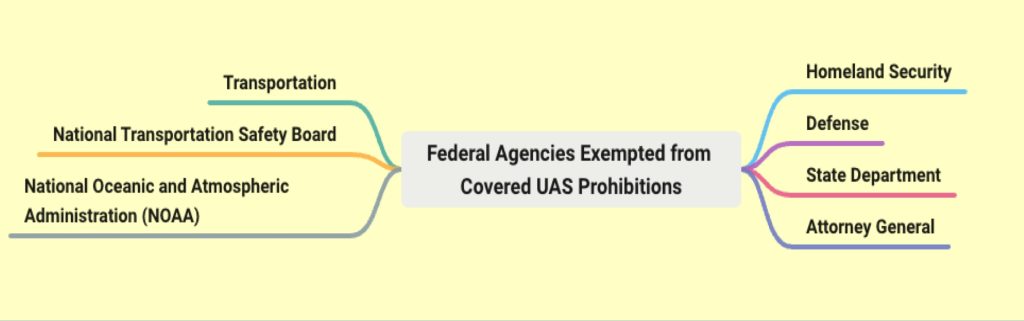

For the less ambitious readers (or lazy journalists), Bathrick prefaces the 36-page analysis with a cheat sheet replete with exemptions and waiver conditions. Those hypothetical “outs” occupy nearly half of the section, and are described as open to “Secretaries of Homeland Security (DHS), Defense (DOD), State (DOS), and the Attorney General (DOJ) if the following applies to the procurement or operation.”

Conditions immediately detailed relate to the effective functioning of programs in “the national interest.” That qualifier potentially covers quite a lot of ground, given the law enforcement, counter-terrorism, airspace protection, critical infrastructure inspection, and myriad other activities federal agencies are responsible for on a daily basis – up until recently, mostly using maybe-not-so-banned DJI drones.

Another get-out-of-blacklist-free condition is that “subject UAS cannot transfer to or download data from a covered entity” – information exchanges DJI has said its drone aren’t even capable of when configured by users not to. How hard is that?

Bathrick’s guide also notes “exemptions for State, Local, and Territorial (SLT) law enforcement (LE) and emergency service (ES) agencies,” which the federal government can also help by providing funds or aid for otherwise banned drones that have “received approval or waiver to purchase or operate.”

Why is that significant? Because federal agencies have skirted previous partial blacklisting efforts before, after they’d determined DJI drone were essential to their fulfilling their responsibilities

Indeed, Initial US bans on DJI drones produced a reported 2021 memo penned by Department of Interior insiders, replete with complaints about being stuck with what were described as far more expensive, dramatically less effective US-made options under the anti-China prohibitions.

Reflecting a similar thinking, officials from both the Federal Bureau of Investigations and Department of Homeland Security acknowledged under questioning by legislators their agencies still used DJI UAVs in their work – a preference demonstrated since by numerous local and state police forces launching or renewing drone programs. Politics, it seems, is readily ignored by officials who view performance more critical than posturing, no matter the intensity of anti-China sentiment swirling on the ground.

As a former fighter pilot and government agency veteran, Bathrick’s patriotic bone fides are beyond reproach, and he assiduously avoids making judgments or predictions in reviewing the new law. His document is decidedly neither pro- nor anti-ban.

Still, having long served as director of the Department of the Interior’s Office of Aviation Service during the very period UAV tech was emerging, Bathrick knows a lot about wading through the administrative and legal bog necessary to make operations more effective from the air – certainly more than the, um, drones in Congress.

Indeed, he was the key federal official in recognizing new small craft applications in firefighting, land management, search and rescue, and many other then-untapped uses. His work was also essential in launching those inventive operations in ways that saved taxpayers money, increased the efficiency of government work, and earned public confidence in drones.

So even if the anti-DJI and -Autel law is now on the books – and Bathrick isn’t someone people shout bet on to publicly cheer or deplore it – his new dissection of its different measures represents another public service: letting drone users know how measures politicians are marketing as a blanket ban may play in less absolute terms in reality.

Images: Bathrick Aviation Consultancy

FTC: We use income earning auto affiliate links. More.

Comments