As a reflection of just how strong public sentiment in France remains against police use of drones to monitor people, officials waited well into the nation’s six-straight nights of rioting before giving law enforcement agencies the green light to fly UAVs for security purposes in response to the unrest.

The first authorization of drone flights to provide police aerial views of neighborhoods wracked by rioting were handed down last Thursday, 48 hours after the first incidents of what became nightly violence across France.

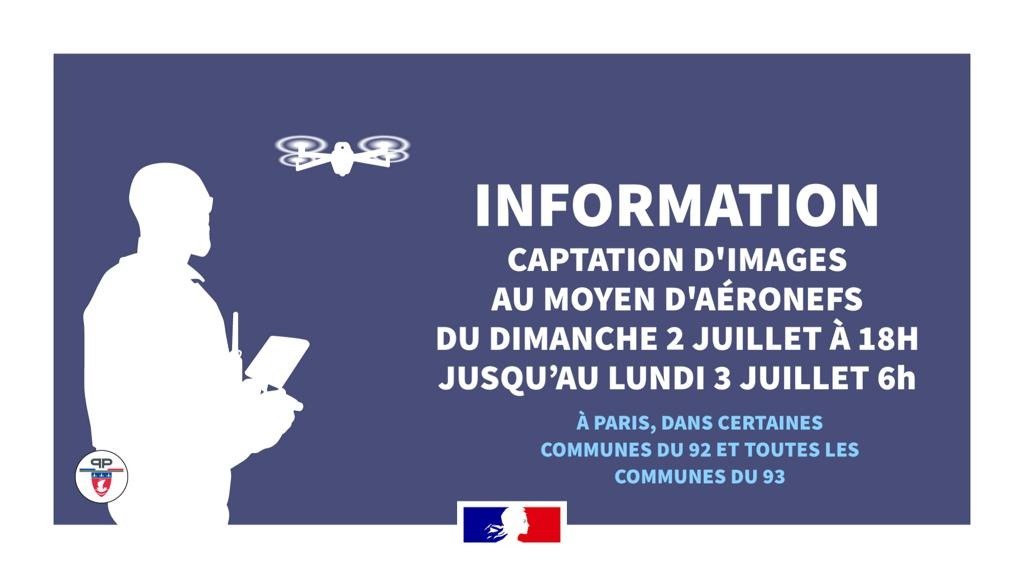

Since then, other regional police prefectures have slowly followed suit, with most finally permitting nighttime drone deployment around major France’s major cities on Saturday. It wasn’t until Sunday – ahead of what became the sixth and reportedly calmest night of unrest – that officials in Paris approved aerial surveillance for the capital and surrounding suburbs.

Why the hesitation to gain elevated perspectives of zones that police were previously entering, often at considerable risk, without that additional situational awareness help?

Because though a decree issued last April established the legal framework for deploying UAVs in law enforcement scenarios, use of drones to monitor France’s public and individual citizens – even those breaking laws – remains widely unpopular.

The social and historical reasons for that wariness are too complex – and, regrettably, prone to outside sarcasm – to detail here. But by and large, they’re rooted in privacy concerns, and fears about the way authorities gathering and storing personal or details today may wind up using them in evolved civil liberty situations tomorrow. Memories of how extensive French police files were tragically used under Nazi occupation remain alive.

Such worries over security officials learning too much about individuals, for example, explain why it’s still illegal for French census taking to include details like race or religious affiliation of respondents.

More recently, French privacy advocates – backed up by the official state data treatment watchdog – have focused attention on the risks posed by information-gathering tech, including UAVs. In 2021, those allies mobilized in protest after police used drones to monitor people on permitted outings during COVID-19 lockdowns – activity to detect potential infractions taken before any rules on drone surveillance had been created.

The result was protest to police using drones to identify people without their explicit consent – arguably one of the main regulatory rules pounded into the mind of anyone taking France’s drone piloting test. That led to legal limitations being put into place that wound up provoking a diplomatic row with the UK, after Paris declared it could no longer use UAVs to monitor French coasts to stop undocumented immigrants from illegally crossing the Channel into England.

Read: Blessed are the pilots: France’s villages turn to drones to steam clean churches

Those setbacks put France’s government into motion to adopt amendments to existing laws to permit drone surveillance by police, while also addressing precise legal challenges raised by privacy opponents. The upshot was a text deemed constitutionally sound last year that was passed and ultimately applied in April.

That statute establishes a clear, sequential chain of command approval required to authorize police drone operation in France. Those missions, moreover, are limited to deployment including “the prevention of attacks on people or property”; “security of assemblies in public places”; “regulation of transport flows”; “border surveillance and illegal crossings”; “rescuing people”; and “the prevention of terrorist acts.” Also detailed are the length of time data gathered by UAVs may be used and stored.

Read: Host of looming global sports events, France echoes FBI fears of drone strike threats

In light of the sustained unrest that by Monday morning had led to 3,000 people being detained for suspected rioting, authorities in France by Saturday had apparently calculated the urgency for police to more effectively respond to and contain nightly violence would outweigh any eventual opposition to police use of drones.

If that was indeed the case, their reasoning appears to have been sound.

Whether it was due to improved situational awareness permitting cops to move in on and subdue rioters – while also avoiding the frequent ambushes that had been set for them – or just coincidence, Sunday night marked a significant drop in unrest across France since rioting began last Tuesday. Thus far, meanwhile, virtually no protest has been voiced to police UAVs at work over the nation’s upended cities.

FTC: We use income earning auto affiliate links. More.

Comments